How Did the Romans Think About Romantic Love?

The word romance derives from the Latin romanicus, meaning in the Roman style. But what we think of as romance and what the ancient Romans thought of it are two very different things. The Romans were not sentimental, and in their hyper-masculine world becoming infatuated with a lover was seen as a kind of madness, an affliction that threatened to undermine a man’s virility and make him prey to those who were weaker than him.

Continue reading

The Central Place of Spectator Sports in the Roman Empire

Ancient Rome was a society that loved sports. From boxing to chariot racing, and Gladiatorial battles to harpastum, an ancient form of rugby, the Roman public couldn’t get enough of sports. Spectator sports provided a sense of belonging, supported a shared ethos, and delivered a welcome diversion to the monotony of everyday life. Sports also gave the emperors a form of social control. Therefore, it is not surprising that the decline of spectator sports in Roman culture coincided with the decline of the Empire itself.

Continue reading

How Realistic is the Movie "Gladiator"?

The laughable Tik Tok myth that most men think about Rome every day no doubt had its roots in Ridley Scott’s film Gladiator (2002). Gladiator was a huge hit and got people talking about the Roman Empire again after decades when it had fallen off the radar of popular conversation. The film itself is well acted, brimming with action, and filled with all sorts of interesting details, from the set design to the costumes. But how realistic is it, really?

Continue reading

Life Inside a Roman Insula

In the 5th century most of Rome's urban population lived in multi-story apartment buildings called insulae. Life in a Roman insula was a raucous, risky affair with neighbors living practically on top of each other and the threat of fire an ever present danger. In this video the folks at Moments in Time take you inside a Roman insula to get a taste of what that experience was like.

Continue reading

Long Before Fox News There Was the Fifth Century Christian Church

Propaganda isn’t just lying and distorting to achieve a political end, it’s also the art of telling people what they want to hear. The fifth century Christian church was a divided and embattled institution trying to survive against schisms within its own polity and a deeply entrenched pagan rival that still held the sympathies of the public. To triumph it had to resort to unscrupulous measures, which meant exploiting the worst instincts of its followers by telling them they were blameless, and others were entirely at fault.

Continue reading

10 Mind Blowing Acts of Sexual Depravity Committed by Roman Emperors

When it comes to the corrupting influence of absolute power, few instances make the point more convincingly than the self-indulgent perversities of the Roman emperors. Free to do whatever they wanted these shameless beasts sunk to levels of depravity that still shock us today. These are 10 mind blowing acts of sexual depravity committed by Roman emperors.

Continue reading

A Pictorial Tour of Ravenna

For 75 years Ravenna was the capital of the Roman Empire and the epicenter of Roman imperial power. With the Fall of the Roman Empire, however, Ravenna declined in population, and today it is a small Italian city of 400,000 people. Yet many of the remnants of its imperial glory remain intact. We visited in September of 2022. This is what we found.

Continue reading

How the Roman Holiday of Saturnalia Morphed into Christmas

Many of the traditions of Saturnalia have come down to us in the form of Christmas traditions. Even Christmas wreaths and Christmas lights were originally parts of Saturnalia. The parallels are surprising. But why, when so many other Christian observances are so somber and solemn, does Christmas retain so many of the merrymaking features of a big, rowdy party?

Continue reading

How the Abandonment of the Roman Virtues Led to the Downfall of the Empire

“Values” are the glue that hold a society together. In the absence of shared values a society becomes like a cancer, the constituent cells turning against each other at the expense of the organism that gives them life. In modern Western societies values have been traditionally conferred through religious traditions. Such was the case in the Roman Empire—until it wasn’t.

Continue reading

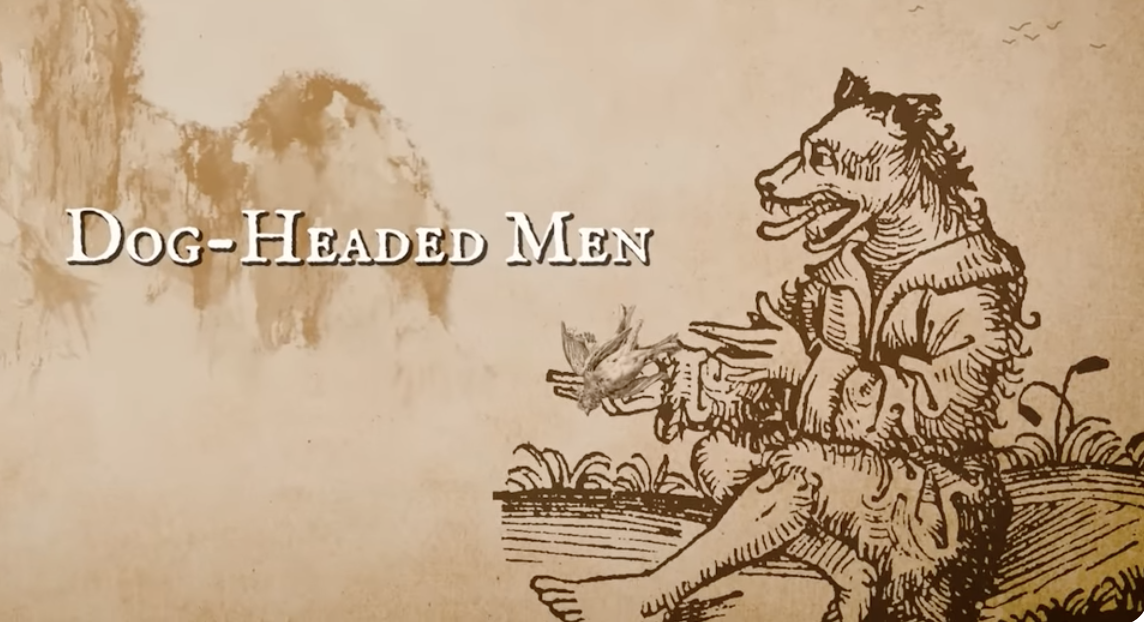

The Outrageously Bizarre Ideas the Ancient Romans Had About India

At its greatest extent the Roman Empire stretched 2,500 miles east from Rome to the Red Sea, but beyond the Red Sea lay a mysterious world the Romans knew almost nothing about. So vague and shadowy was India to the Romans that their theories of what lived there were truly bizarre. This video shows just how far off the mark they were.

Continue reading

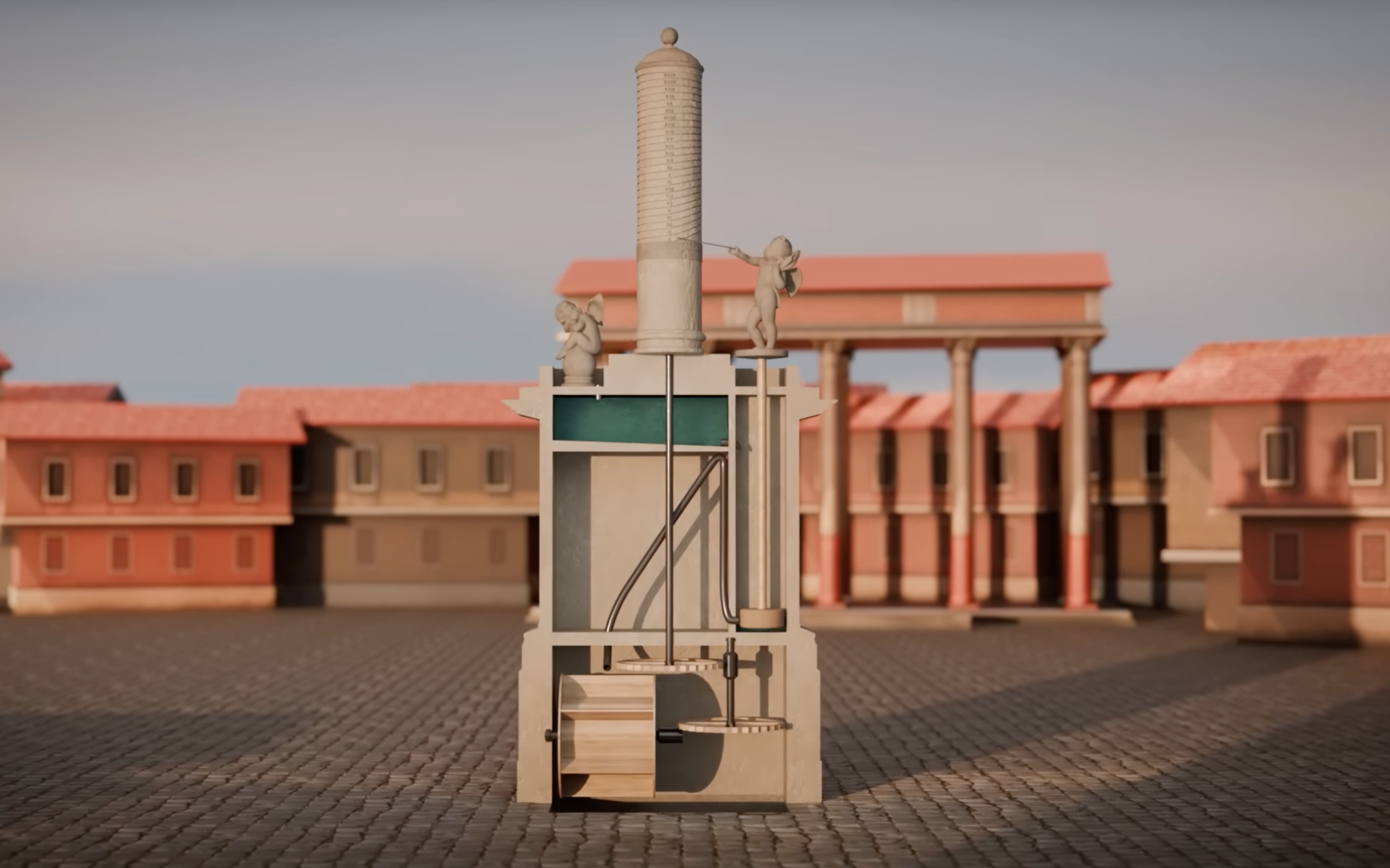

10 Modern Advancements the Romans Had First

Many modern advancements we rely on as part of our every day lives were invented in the last 150 years, but a surprising number of those actually existed in the Roman Empire more than 2,000 years ago and have only just been reinvented in the past century and a half. The Romans were far more advanced than you may think. Here are some surprising examples...

Continue reading

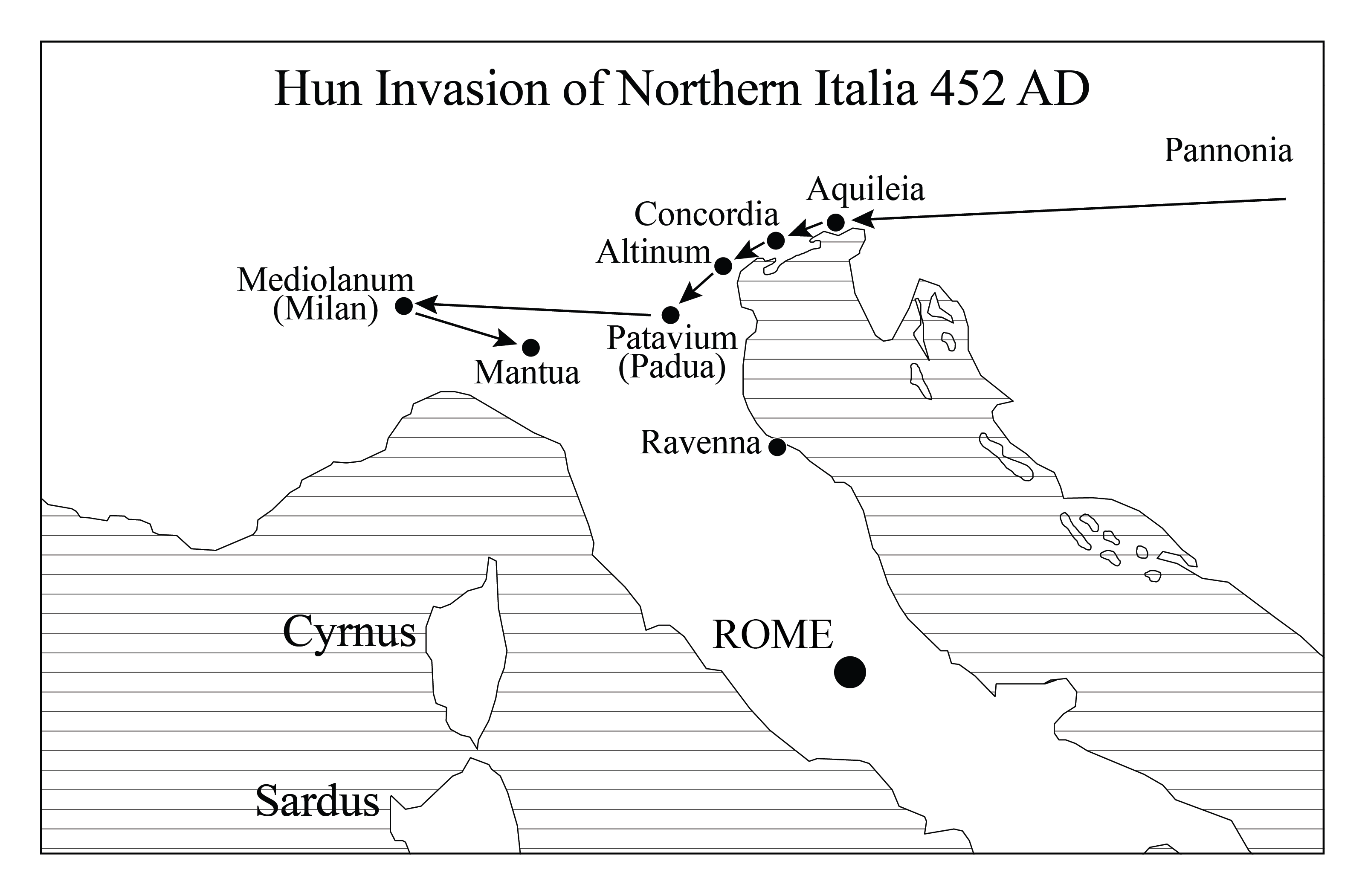

How I Created The Maps For My Novels About the Fall of Rome

One of the more challenging maps I had to come up with was a map of the Huns’ invasion route as they moved west across central Europe into Gaul. To construct the map I had to locate each town the Huns sacked along the way, and there were a lot of them. Then I had to figure out what those towns are called today...

Continue reading